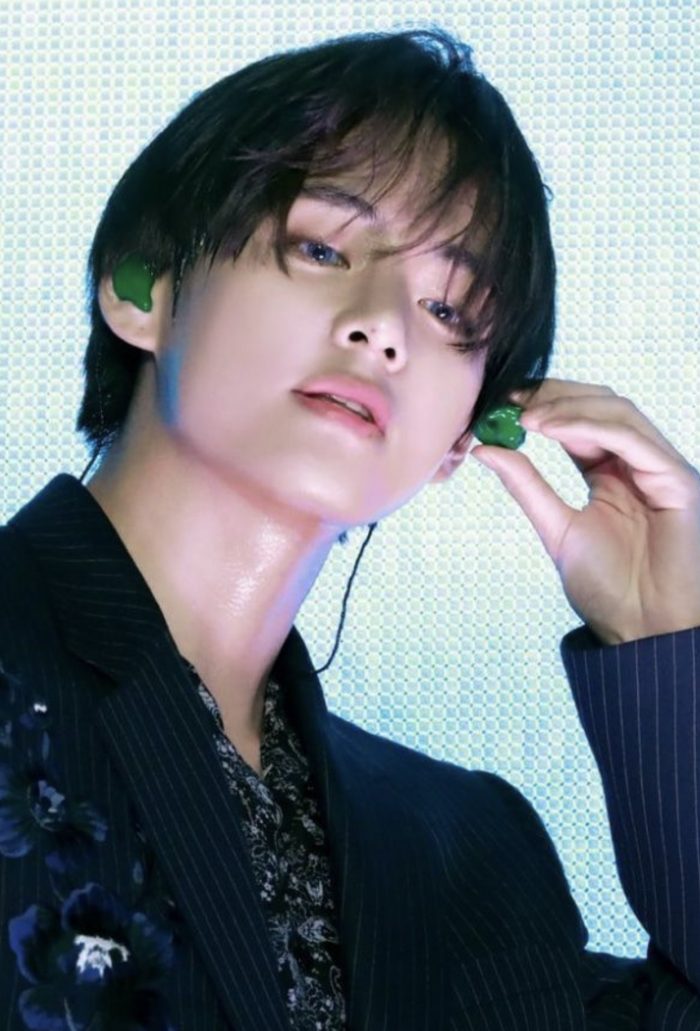

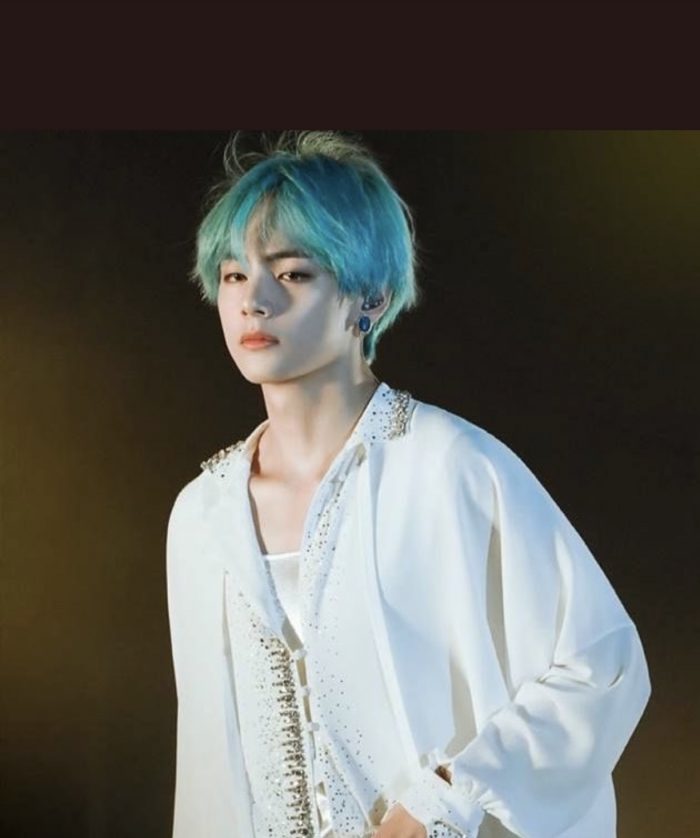

BTS_2 “Kim Taehyung”_2

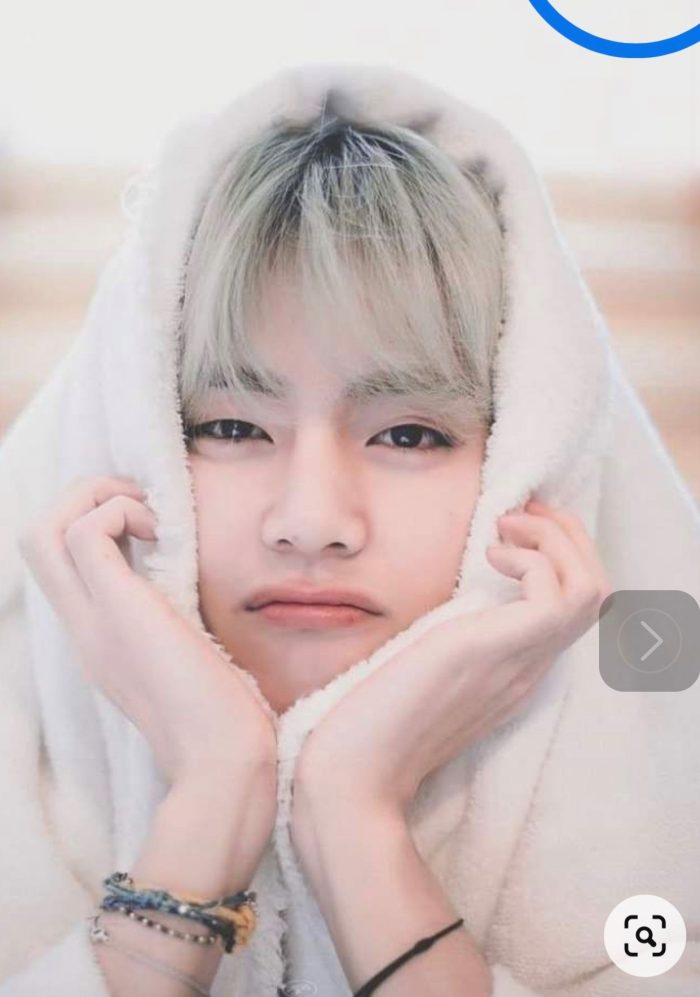

2021/3/19 ❄ これまでの写真より(Waering white, maybe from young age to recent)

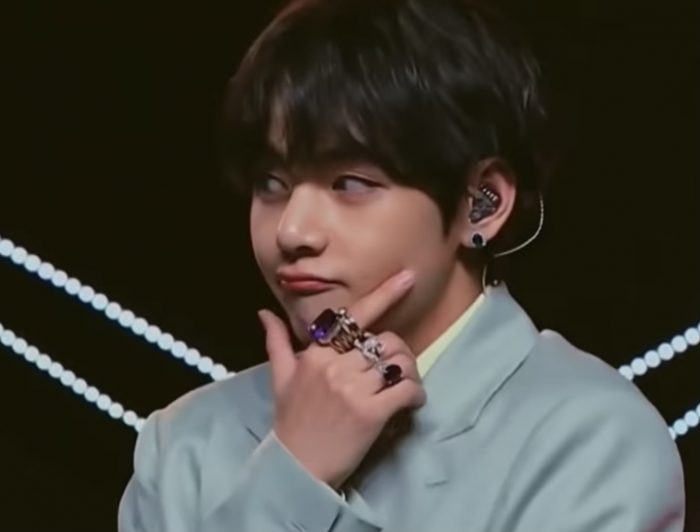

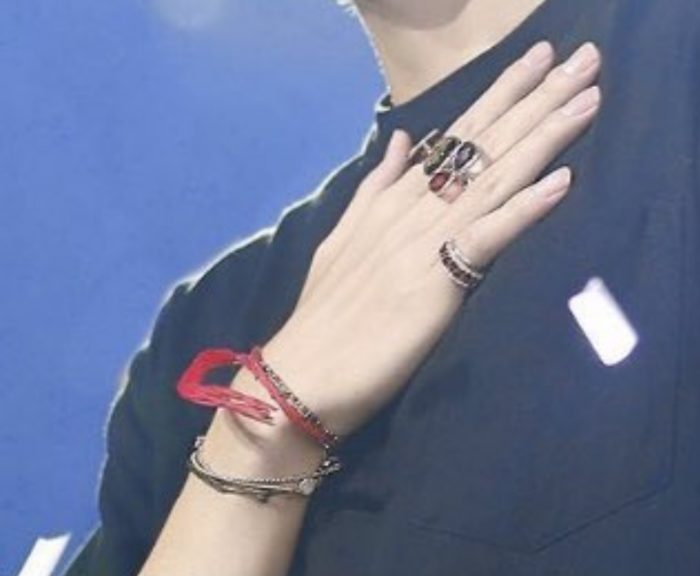

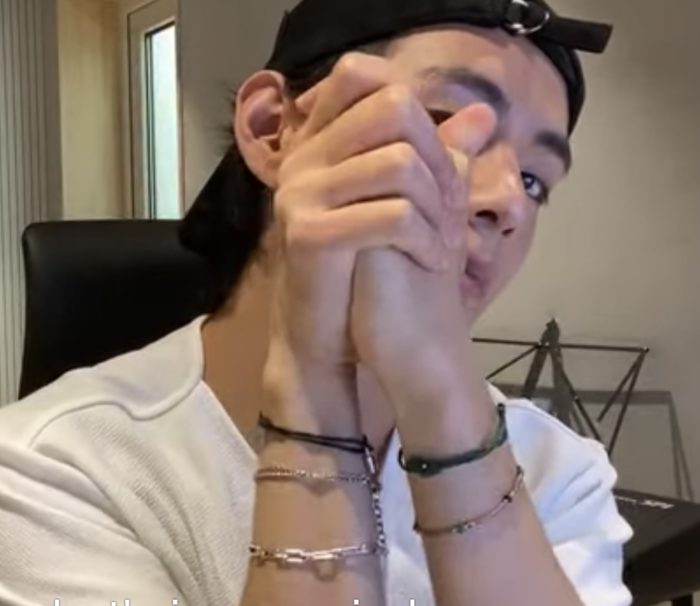

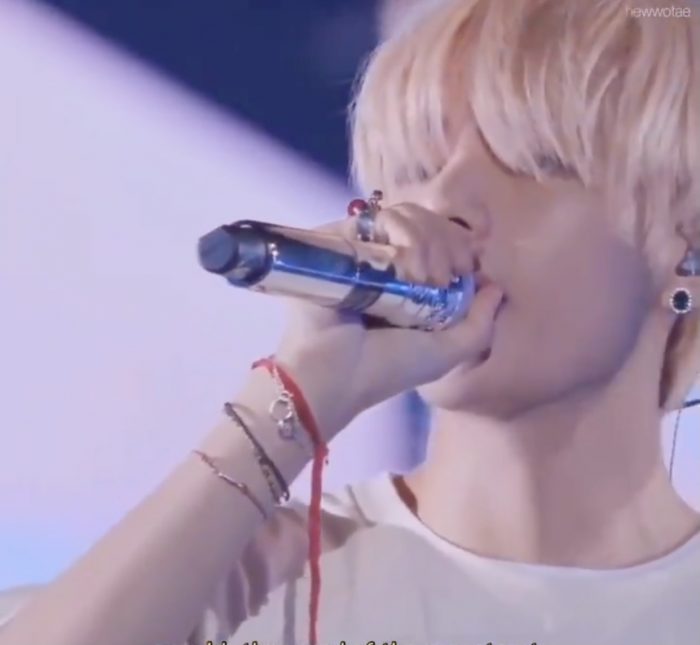

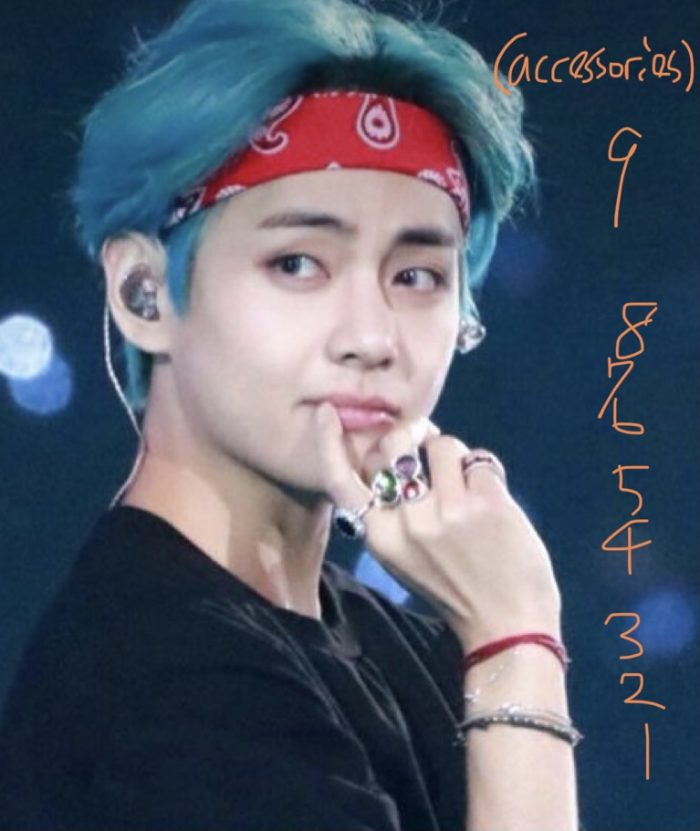

手首と指にこんなにたくさんアクセサリーをつけてる!

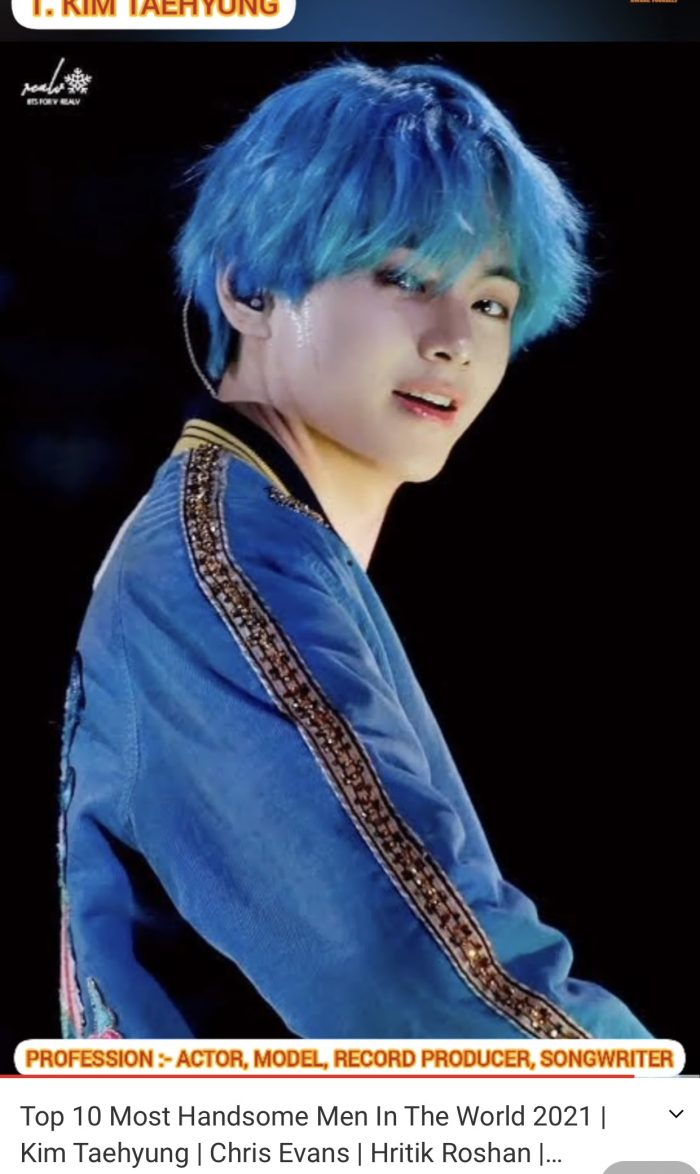

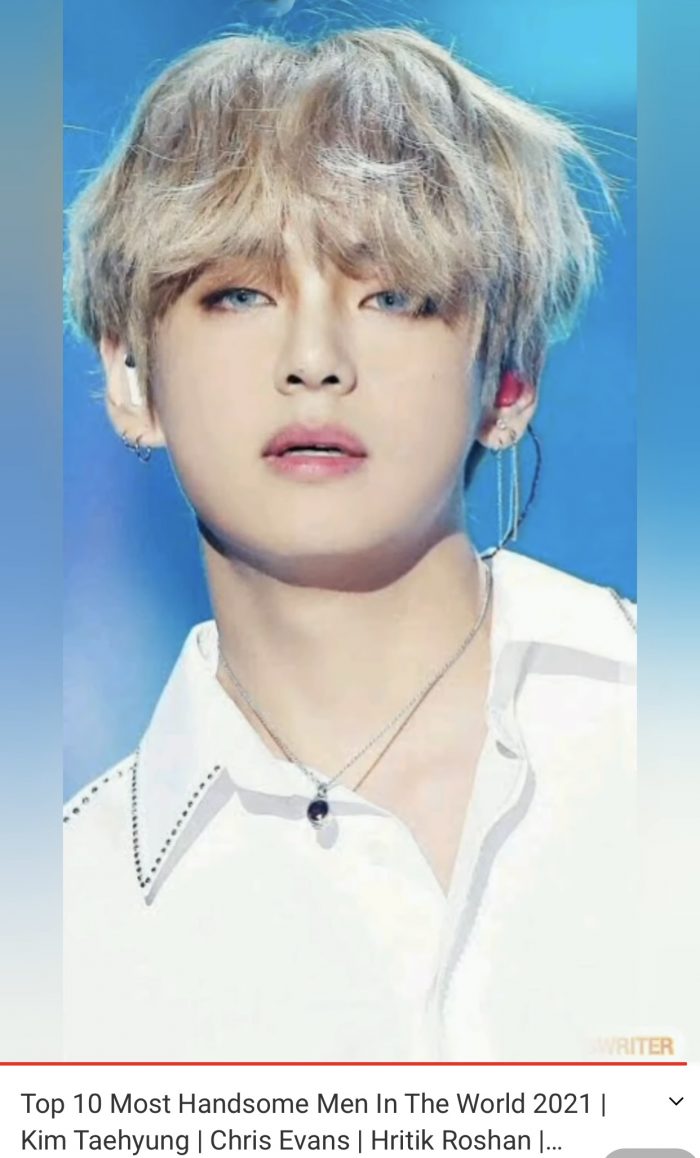

Most Handsome Man in the World, No. 1! (It’s good but I wonder who chose them?)

Top 10 Most Handsome Men In The World (2021 updated)

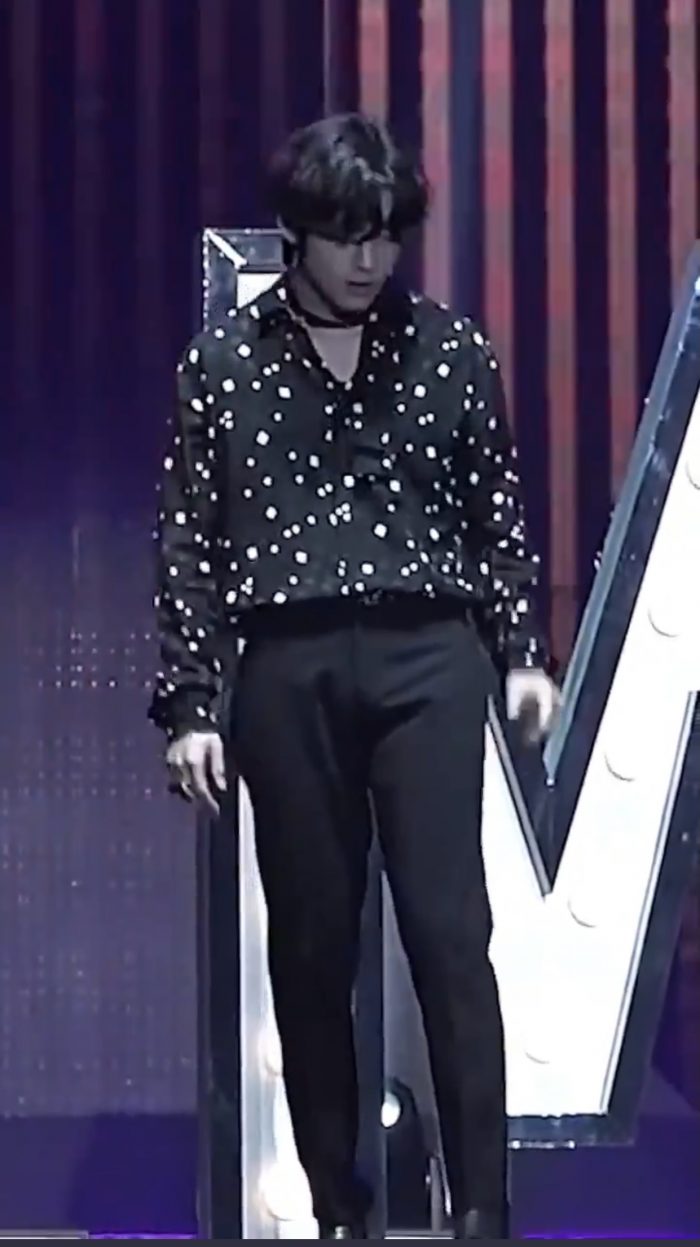

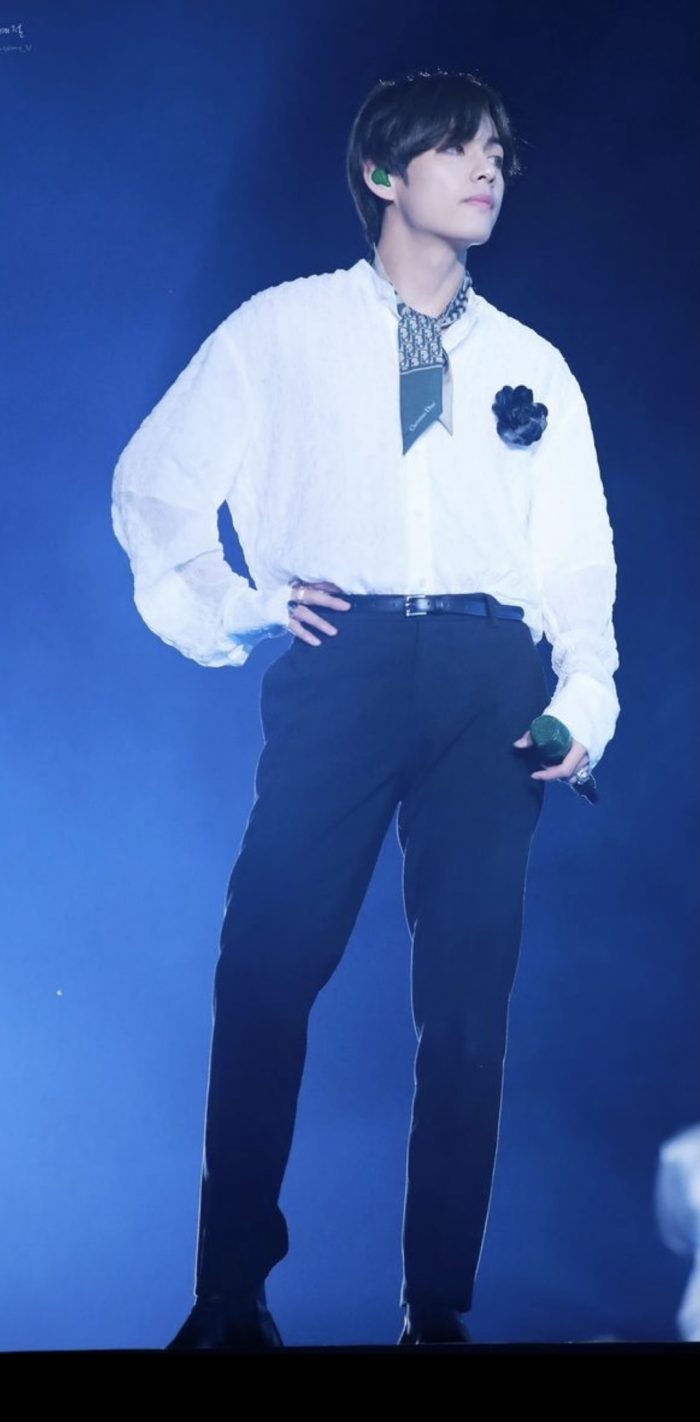

[방탄소년단 뷔] 신라의 화랑 한성이 안뇽👋 (방방콘 깨알컷)

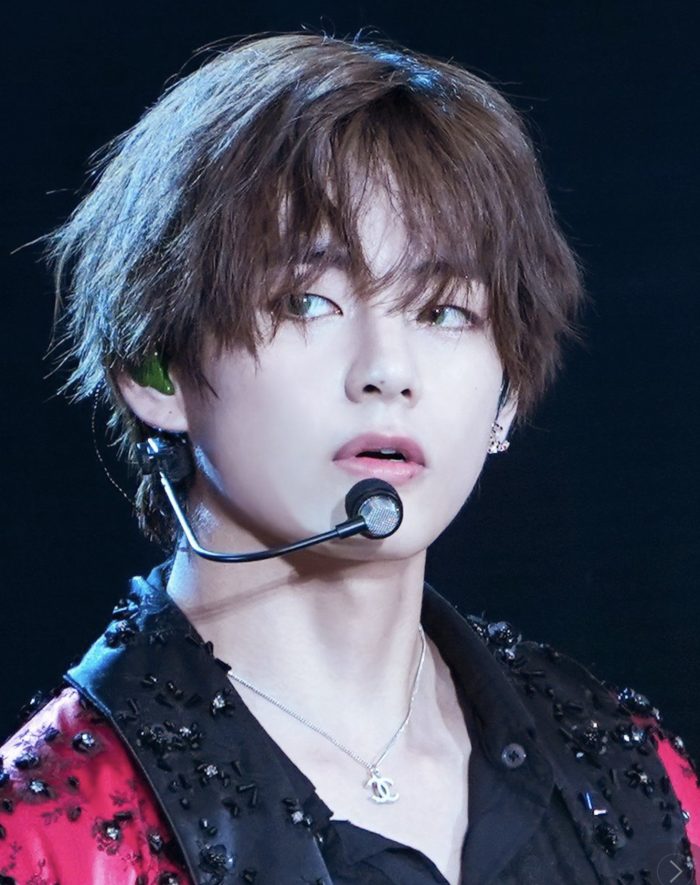

When Kim Taehyung Went all Out in a Concert (Watch at your Own Risk)

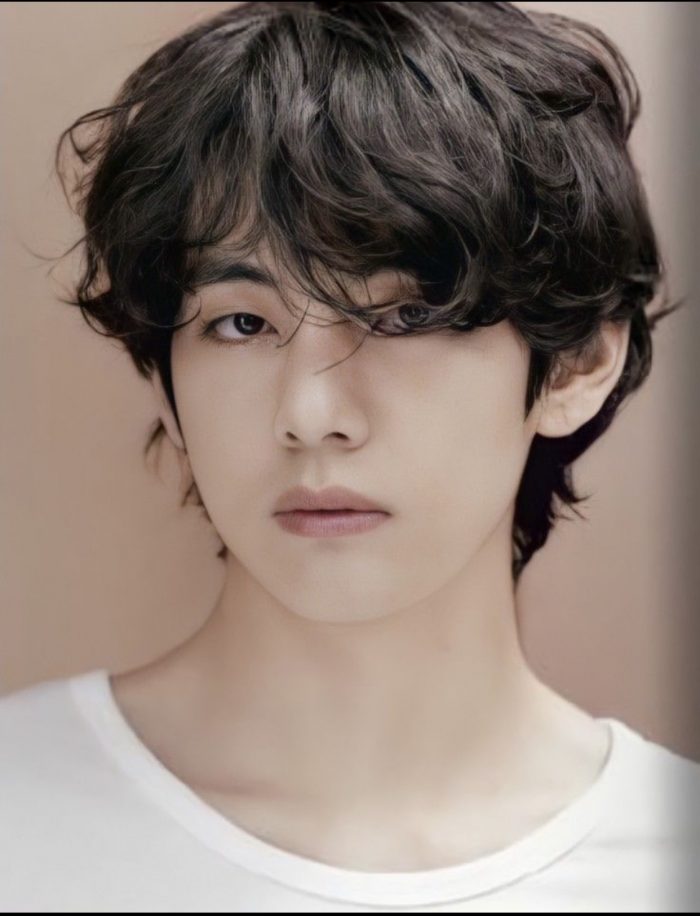

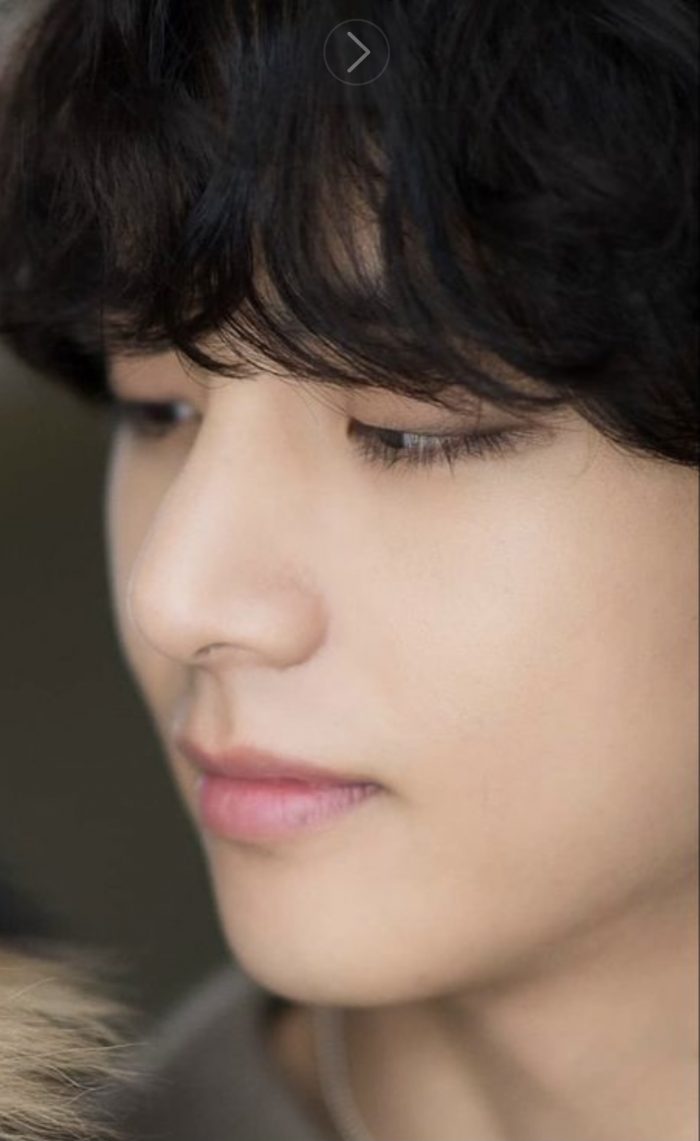

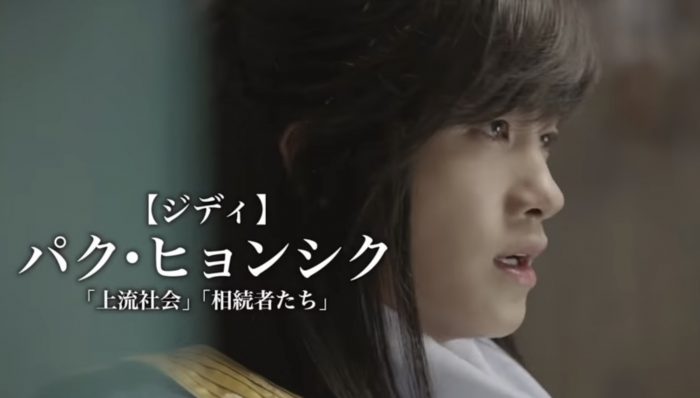

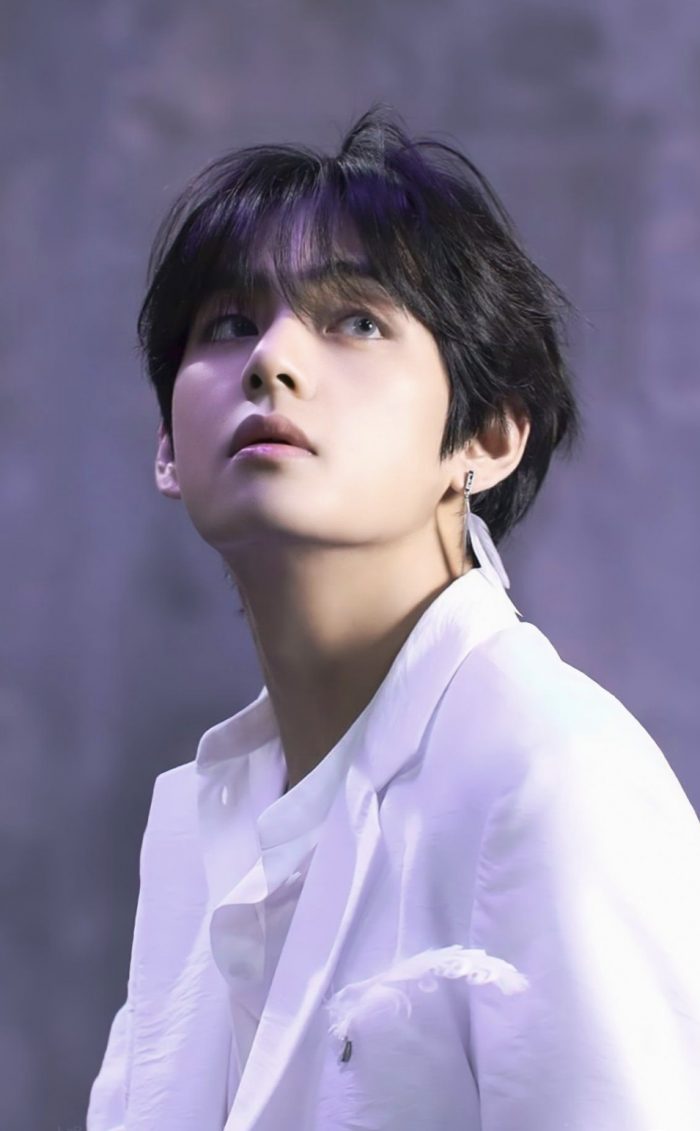

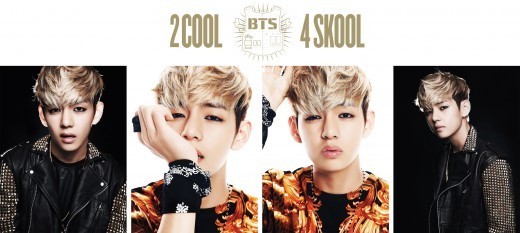

防弾少年団、19歳の美少年「V」を初公開…12日デビューシングルを発売

TVREPORT | 2013年06月03日 (Kstyleより)

写真=Big Hitエンターテインメント

写真=Big Hitエンターテインメント

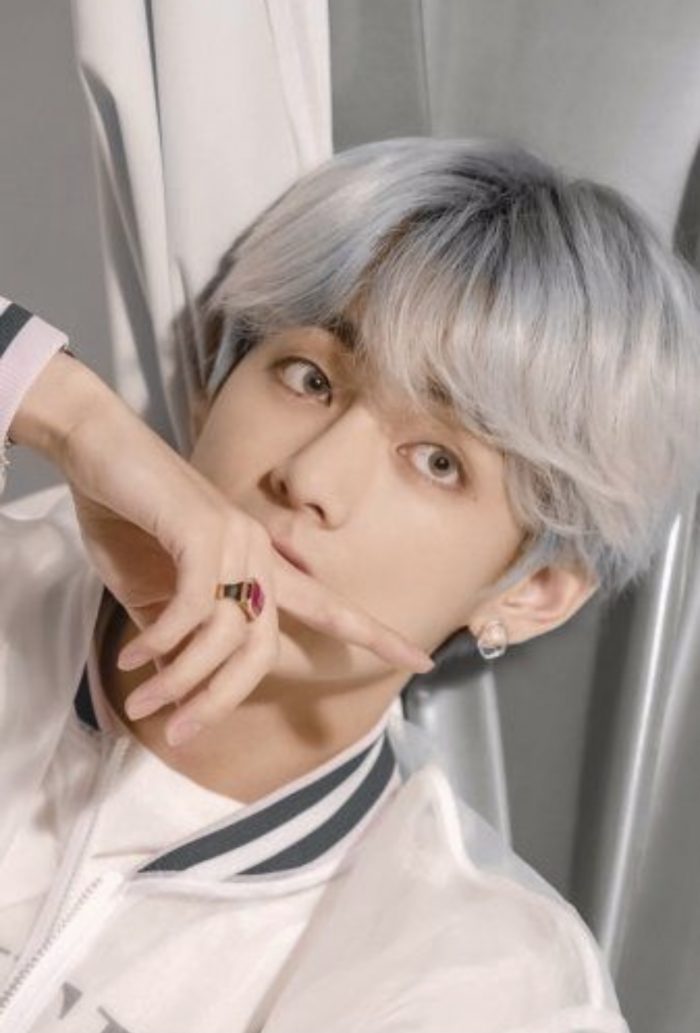

デビューを控えているヒップホップアイドルグループの防弾少年団が、19歳の美少年メンバーV(ブイ)の写真を公開した。3日、防弾少年団の所属事務所側は、公式ホームページにVの写真4枚を掲載した。防弾少年団はすでにデビュー前からブログを通じてファンとコミュニケーションしてきたが、Vの姿は一度も公開されていない状況だった。

Vはエキゾチックな顔立ちが印象的な19歳の美少年で、グループでボーカルを担当している。魅力的な重低音の持ち主で、サックスを学んだ履歴を持っている。 <16歳のはず!>